The Boston commute has always been a nightmare, but by the later 19th century it had reached its high mark. The city was experiencing a massive population surge that pushed it's transportation infrastructure to the very limits of sustainability. Hundreds of new immigrants were arriving daily and settling in the already over-populated inner neighborhoods. Tremont Street, the main thoroughfare, was a near-constant gridlock of foot traffic, horse carts and electric streetcars. The surrounding maze of narrow, winding streets became impassable. And the various steam-powered train lines that carried suburban commuters into the city each day created a tangled web of crosstown and inner city routes that added to the chaos.1

The breaking point would be The Great Blizzard of 1888, one of the most severe snowstorms to ever hit the United States.2 The massive storm wreaked havoc up and down the East Coast and completely paralyzed the city of Boston. Trains and street cars were immobilized by massive 50-foot snow drifts, telegraph lines went down, and hundreds of people were stranded for days without food, water or heat. Passengers trapped in the railroad cars burned the seats to stay warm. Others attempted to brave the freezing temperatures and 80mph wind gusts and tried walking home on foot but were quickly disoriented, or else stuck in the drifts. Some froze to death. In the aftermath of this catastrophe it became clear that the city needed to modernize its public transit.

The city responded by forming the Boston Transit Commission, which tasked a team of engineers to design an inter-connected transit system that would include both elevated rail lines and an underground subway network.3 The Tremont Street Subway line would be the first phase of this network, and include three stations – Park Street, Boylston and Public Garden (now Arlington Street). When the construction was finally completed, it would be celebrated as an engineering first in the United States.

But there is a dark side to this project that seldom gets mentioned in the history books.

FEAR OF THE DARK

"I don't believe in a tunnel or a subway. I expect to be a long time underground after I am dead, but while I live I want to travel on the earth, not under it."

– I.W. Sprague, local undertaker (The Boston Globe, July 25, 1894)

From the very beginning, the subway

project was marred by controversy and protest. At the time,

subterranean travel still carried a strong psychological stigma. Many

people associated the underground regions with death, decay and evil

spirits. It was also considered to be the unsanitary habitat of

snakes, rats, insects, germs, fungus and who knows what else.

As Boston historian Charles Bahne notes, at this time it was still largely uncharted territory and thought of as

"the realm of Lucifer himself, inhabited by lost souls,

moldering corpses, strange forms of animal life, and noxious vapors."4

From the very beginning, the subway

project was marred by controversy and protest. At the time,

subterranean travel still carried a strong psychological stigma. Many

people associated the underground regions with death, decay and evil

spirits. It was also considered to be the unsanitary habitat of

snakes, rats, insects, germs, fungus and who knows what else.

As Boston historian Charles Bahne notes, at this time it was still largely uncharted territory and thought of as

"the realm of Lucifer himself, inhabited by lost souls,

moldering corpses, strange forms of animal life, and noxious vapors."4Playing on these fears, the newly formed Anti-Subway League argued that the project posed a serious threat to public health as mold, mildew, and germs would infect commuters with respiratory ailments, and rodents and snakes would be driven to the surface and plague the city. The group submitted a petition signed by twelve-thousand people opposing "any subway in any portion of the City of Boston".5 The Boston Post supported the League's claims with a sensationalist editorial entitled ''Hideous Germs Lurk in the Underground Air," which warned of the dangerous “subway microbes” that would plague the subway tunnel and sicken commuters. The article was accompanied by an artist's sketch of a magnified “microbe”, depicting a gruesome, slimy, multi-headed monster, which helped fuel the popular unease.6 Despite continued opposition, the planned subway project narrowly passed by a public referendum and work soon began.7

On March 29, 1895, a solemn ceremony took place and ground was finally broken on the Tremont Street Subway project. But by this time the negative stigma and health concerns associated with it had already become ingrained in the public consciousness. As the excavation began, residents from the surrounding area claimed that “subway filth” was poisoning trees in the Public Garden. According to an article in The Daily Advertiser: “Wherever the earth dredged up from the subway cribs has been spread over the ground, the trees have been sickened. Some of them have died. Why should this foul, poisonous sod be laid out in the city's parks to perfume the neighborhood and spread disease germs over the surrounding regions?”.8

In addition to the public grumblings, accidents seemed to plague the project from the very start. During the first weeks of digging a water main was ruptured and the nearby Park Street Church was covered with mud and debris. Preaching from the pulpit, the pastor of the church damned the project site, referring to it as the “infernal hole” and an “un-Christian outrage”. He concluded his fiery sermon by asking congregants, “Who is the boss in charge of the work? Is it the Devil?”.9

A MACABRE DISCOVERY

As the tunnel excavation progressed

along Tremont Street, workers came up against their next major

obstacle: The Central Burying Ground. It was accepted that the subway

line would pass through a portion of the old cemetery. There was no

way around it. But it was thought that only a few graves would be

displaced by the project. However, things didn't exactly go as

planned.

The Central Burying Ground sits on the south side of the Boston Common, along Boylston Street. It was established in 1756 to alleviate overcrowding at the nearby Copp's Hill, King's Chapel and Granary burying grounds, and generally considered to be the least desirable since it was located the farthest from the market center.

By the time of the subway excavations, the cemetery was already old enough for many of its inmates' identities to be lost or otherwise unknown. Its thought that casualties from the Battle of Bunker Hill are buried there, as well as British soldiers who died during the Siege of Boston (1775-76). It's also one of the few cemeteries where Roman Catholics could reside at the time, and provided a final resting place for some of the city's earliest immigrants (sometimes referred to as “strangers” in the scant burial records). The Central Burying Ground itself eventually became so crowded that gravediggers petitioned the city, complaining that they were forced to bury dead bodies four-deep to a grave.10

In 1826, Mayor Josiah Quincy finally closed the cemetery, passing an ordinance that banned digging new graves or building additional tombs. This was both a response to the overcrowding and a reflection of the broader shift in attitudes towards interment, where corpses began to be viewed as a hygienic danger to the public and burial grounds were moved to the city outskirts.11

It was bad enough that the subway tunnel would need to pass through the heavily occupied, disorganized and poorly marked graves of the Central Burying Ground. It would also have to navigate the entire length of the Boston Common's south side – which, as it turned out, was itself one massive burial site. A few months prior to the excavations, workers came across a number of human bones just outside of the cemetery grounds when they were burying some electric wires along the Boylston Street Mall.12 This should have given some indication of what could be expected during further excavations of the area. But no one could have anticipated the massive scale of human remains that would be unearthed in the coming months.

Although New England is known for its old colonial cemeteries, most of the early settlers were in fact buried in unmarked public graves. Since it was established in 1634, the Boston Common provided a convenient burial spot for much of the city's lower classes. Under the early Puritan regime, untold numbers of undesirables – murderers, thieves, pirates, Native Americans, military deserters, Quakers and witches – were executed and piled into anonymous pits here.13 Later generations of the city's poor, particularly during outbreaks of disease, were also laid to rest on the Common grounds. Those who died in the city's almshouses, public hospitals or in the streets were generally deposited in anonymous mass graves and covered in quicklime with little to no record of their passing left behind.14

It wasn't until 1810, when the city passed a law regarding burial practices (“Regulations for establishing the Police of the Burying Grounds and Cemeteries, and for Regulating the Burial of the Dead, within the town of Boston”), that an ordered system in the disposal of the dead was finally established.15

In and around the Central Burying Grounds, and throughout the surrounding area of the Boston Common, tunneling crews came across countless unmarked graves. The first bones were discovered when a medical student was walking through the construction site and stepped on something that made a loud snap. After kicking away some dirt he reached down and picked up the object, which turned out to be a human thighbone. Further digging around uncovered a skull, the disjointed parts of two arms and hands, and other bone fragments. Workers continued to find human remains the following day, and began piling them carelessly against a retaining fence. By that evening, vandals had broken into the worksite and pulled a skull and a number of bones from the open tomb and paraded them through the Common.16 The local newspapers jumped on the story, condemning "the desecration of the Old Boston Cemetery" and placing full blame on the Boston Transit Commission.

Day after day, curious residents lined up along Tremont Street to watch the removal of these skeletal remains. However, as the weather got warmer, the worksite was overtaken by the stench of decomposition and it became necessary to keep the crowds away. To alleviate the health concerns of an already unsettled public, the Boston Transit Commission was forced to issue a statement, which argued, “the earth is a good disinfectant, and a burial of more than half a century would destroy any germs of disease that might still linger after death.”17

After nearly seven months of grim excavations it was estimated that the portions of between 900 and 1,000 bodies had been dug up and would need to be re-interred.18 The Daily Advertiser continued to preach condemnations. "They have sacrificed the Common, which is the playground of Boston," according to a scathing editorial, "and now it seems that the dead are not to be allowed to rest quietly in their graves. The subway must pass through the Boston Common, even if sacrilegious hands are to be laid on the dust of Boston's historic dead."19

Overwhelmed by the sheer number of human remains on its hands, the Commission appointed Dr. Samuel A. Green, a librarian from the Massachusetts Historical and Genealogical Society, with the daunting task of directing the re-interment process.20 All told, nearly seventy-five boxes – each containing a miscellaneous assortment of bones – were prepared and eventually buried in a mass grave on the northwest side of the Central Burying Ground. The site is marked by a single stone tablet that reads "Here Were Re-interred the Remains of Persons Found Under the Boylston Street Mall During the Digging of the Subway, 1895".21

TRAGEDY AND DISASTER

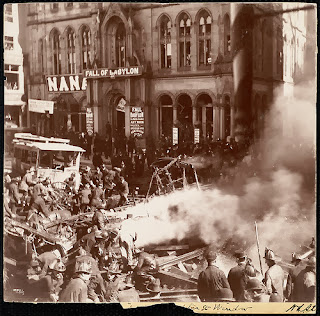

On March 4, 1897, six months prior to

the scheduled opening of the Tremont Street Subway line, the

seemingly cursed project was met by total disaster when a spark from

a streetcar ignited gas leaking from a pipe that was damaged during the

tunnel excavation. A massive explosion ripped through the

intersection of Tremont and Boylston streets, shattering the windows

of every nearby building and leaving the streetcar “a tangled,

burning hulk, its passengers trapped in and under the debris.” Two

other streetcars were also badly damaged, with bloodied passengers,

by-standers, and horses strewn throughout the area. Ten people died,

and more than fifty were badly injured in the explosion. Hundreds

of onlookers gathered as firefighters attempted to douse the

eight-foot flames that shot up from the street. According to one

report, “it looked as if the whole subway at that

section was aflame.” Eventually the gas main was shut off and the

fire was put out.22

In the aftermath it was determined that the explosion was caused when a gas pipe located between the ceiling of the subway tunnel and temporary planking on the streets had been ruptured by workers. Apparently the pipe had been leaking for some time, filling the gap with a highly combustible mixture of gas and air, before it ignited and caused the massive explosion. While the press and public argued over who was responsible for this disaster, city officials scrambled to re-assure people that no further gas fumes were leaking into the tunnel and that they would be safe on underground trains when the subway system opened. “While the accident was due indirectly to construction work in connection with the subway," according to the press statement, "it does not give the slightest cause for any apprehension as to the safety of the subway for use by the public.”23

The public remained unconvinced.

In the aftermath it was determined that the explosion was caused when a gas pipe located between the ceiling of the subway tunnel and temporary planking on the streets had been ruptured by workers. Apparently the pipe had been leaking for some time, filling the gap with a highly combustible mixture of gas and air, before it ignited and caused the massive explosion. While the press and public argued over who was responsible for this disaster, city officials scrambled to re-assure people that no further gas fumes were leaking into the tunnel and that they would be safe on underground trains when the subway system opened. “While the accident was due indirectly to construction work in connection with the subway," according to the press statement, "it does not give the slightest cause for any apprehension as to the safety of the subway for use by the public.”23

The public remained unconvinced.

Two and a half years after the

initial groundbreaking, the Tremont Street Subway line project –

America's first subway system – was completed. On September 1,

1897, the first underground trolley carried a hundred passengers between Park

Street and Public Garden stations for it's inaugural ride. To calm

the public's fear of traveling underground, the tunnel's interior was

painted white and lit up by electric lamps placed every few feet.24 Most people marveled at this new wonder, and lined up to ride a subway trolley (it's estimated tens of thousands by the day's end). But many still held to their

fears and prejudices.

The stigma of death had tainted the public's perception of the subway so deeply that even the station entrances came up for criticism for their “tomb-like” appearance. According to one critic, quoted in a New York Sun article reporting on the subway's grand opening: “They somewhat resemble the plainer types of mausoleums that are seen in the cemeteries of Paris. All they lack is a carved name on the front and a few death's heads or griffins in granite to make them look a little more grim and gruesome”.25

Even to the present day there is an ominous feeling about this stretch of the subway network, which many consider to be haunted by the ghosts of the past (most notably, that of a British redcoat soldier sighted in the tunnel between Arlington and Boylston stations).26 With the public executions, disease, poverty and despair associated with the buried dead on the Boston Common, the upturned graves of the Central Burying Ground and surrounding area, and the devastating gas explosion tragedy, its no surprise.

The stigma of death had tainted the public's perception of the subway so deeply that even the station entrances came up for criticism for their “tomb-like” appearance. According to one critic, quoted in a New York Sun article reporting on the subway's grand opening: “They somewhat resemble the plainer types of mausoleums that are seen in the cemeteries of Paris. All they lack is a carved name on the front and a few death's heads or griffins in granite to make them look a little more grim and gruesome”.25

Even to the present day there is an ominous feeling about this stretch of the subway network, which many consider to be haunted by the ghosts of the past (most notably, that of a British redcoat soldier sighted in the tunnel between Arlington and Boylston stations).26 With the public executions, disease, poverty and despair associated with the buried dead on the Boston Common, the upturned graves of the Central Burying Ground and surrounding area, and the devastating gas explosion tragedy, its no surprise.

1 Charles Cheape, Moving the Masses: Urban Public Transit in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980), 109.

2 Judd Caplovich, Blizzard! The Great Storm of ‘88 (Vernon, CT: Vero Publishing, 1987).

3 Brett Hansen, "Moving the Massachusetts Masses: Boston's Subway," Civil Engineering Magazine, Volume 79, Issue 9 (September 2009).

4 Stephen Puelo, A City So Grand: The Rise of an American Metropolis, Boston 1850-1900 (Boston: Beacon Press, 2011), 228.

5 Puelo, 229.

6 Joe McKendry, Beneath the Streets of Boston: Building America's First Subway (Boston: David R. Godine Publishing, 2005), 23.

7 Hansen.

8 Puleo, 231-32.

9 Puelo, 236.

10 Samuel E. Turnbull, "The Subway," National Magazine, Volume 2 (1895): 16.

11 Gary Laderman, The Sacred Remains: American Attitudes Toward Death, 1799-1883 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 9.

12 Ogden Codman, Gravestone Inscriptions and Records of Tomb Burials in the Central Burying Ground, Boston Common, and Inscriptions in the South Burying Ground, Boston (Salem, MA: The Essex Institute, 1917), 7.

13 Holly Nadler, Ghosts of Boston Town: Three Centuries of True Hauntings (Camden, ME: Down East Books, 2002), 113-14.

14 Laderman, 41-42.

15 Laderman, 47-48.

16 Puleo, 226.

17 Turnbull, 162.

18 Codman, 7.

19 Puleo, 227.

20 Turnbull, 159.

21 Puelo, 227-28.

22 Puelo, 237.

23 Puelo, 239.

24 Hansen.

25 Puleo, 236.

26 Sam Baltrusis, Ghosts of Boston: Haunts of the Hub (Stroud, UK: The History Press, 2012).

No comments:

Post a Comment